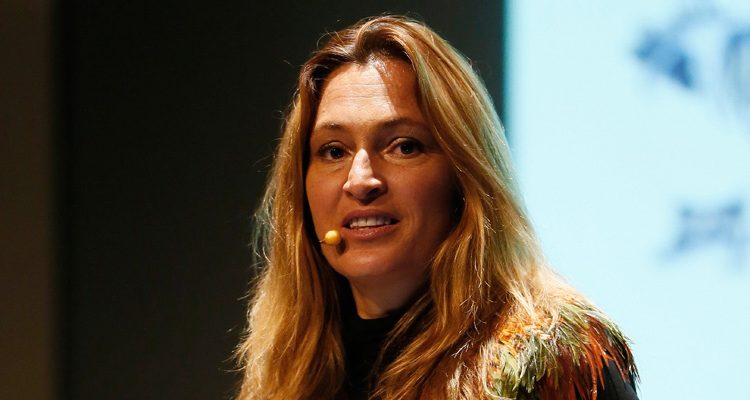

Q&A with Saba Douglas-Hamilton; 2019 and the future of elephants

Saba Douglas-Hamilton is an anthropologist, elephant conservationist and safari camp owner in Samburu, Kenya. Ahead of her UK tour in April, we asked our Facebook fans to suggest some questions for Saba. Here are the Q&A’s.

-

When is the best time to visit Samburu to see elephants – are there different behaviours at different times of the year?

My favourite time in Samburu is just after the rains – Dec/Jan or May/June – when the landscape is verdant green and the herbivores fat and happy. It’s when elephants can be seen in great numbers with the biggest bulls in musth, lots of babies being born and females coming into oestrus. In the dry season the herds break up into smaller units, close female relatives with their offspring, or, when times are really tough, right down to their natal units, as they have to cover greater areas in search of food and water. But the dry season is when the predators come into their own, with lots of cubs born and fat happy cats feasting on weakened prey, which, in turn, improves the health of the ecosystem.

-

Has the ban on ivory trade in countries such as China, the UK and US had visible and significant impact yet, in terms of reducing elephant poaching?

The high price of ivory in China has been the ultimate driver of the poaching of elephants in Africa. After the Chinese government announced that they would be banning the ivory trade within their borders, the price fell from over $2,000 a kilo to just over $700 a kilo. While there are other factors – like the state of the Chinese economy – this is good news for elephants. Together with work being done across the continent to train and equip rangers, reform legal processes and take down organised crime networks behind the smuggling of ivory, we’ve seen great progress made in some key countries like Kenya, and even some tough areas in the DRC like Garamba National Park. But plenty of challenges remain – the desert elephants of Mali are hanging on by a thread in the midst of an Islamist uprising, and the last remaining stronghold of forest elephants in Gabon is under siege.

-

If we could only do or change just one thing for the future of elephants / planet, what would it be?

In my mind, two of the biggest challenges we face are how to curb the growing human population and how to reduce our pathological rate of consumption to a sustainable level. The most humane way to stabilise population is through family planning, liberating women across the globe from the tyranny of uncontrolled reproduction. These efforts would be much more effective if governments started addressing the issue head on, encouraging citizens to have smaller families and significantly rewarding those that did so. The more complicated issue, of course, is how to change the focus of our socio-political system, mired as it is in the capitalist notion that the economy must always grow. We ignore the fact that we live on a finite planet at our peril, and while it may be convenient to let business progress as usual within a four year voting cycle, we need only look to history to note that environmental degradation has often led to the collapse of the most powerful societies. So while human intelligence and technological ingenuity might buy our global community some time, in the long-term a habitable planet is critical for our survival and we have to make that goal our priority. So protecting biodiversity and improving the resilience of natural systems is paramount. The good news is that we can each make a difference by committing to honour the environment every day, starting with small steps at home and in our own back yard.

-

How many visitors to a wildlife area is too many visitors for conservation?

It’s a tricky balance. On the one hand, many of the areas that contain the most biodiversity are chronically short of funds for conservation. Eco-tourism is often touted as a solution, but if it is not well managed and accountable, then inevitably an excess of people coming into wild areas can cause its own set of problems. Yet exposure to different landscapes, ways of life and cultures through travel, connects hearts and minds. People protect what they love, and understanding that the world is different, in pain or needing, beyond one’s immediate horizon has led to tremendous acts of generosity and compassion. I am a great believer in the power of the individual to make change, and this applies as much to how we travel or spend our money as to the way we bring up our children. After all, one can only lead by example. In my view, this means always asking the best of oneself – standing by one’s principles, speaking up when others are silent, or reining in one’s sense of entitlement. So one must choose carefully and support travel agents, tourism operators or NGOs with rock solid environmental principles and a track record of transparency, accountability and conservation success. My hope is that by working together we can move beyond zero impact to positive impact by joining hands and giving something back to the wilderness.

-

How do you get local communities to buy into conservation of iconic species when they raid crops or eat their livestock?

It’s a long process that needs to be addressed at many different levels. Finding clever ways to mitigate conflict is key. The Save the Elephants beehive-fence project in Tsavo is a good example of how insights into elephant behaviour can be used as an effective tool to reduce incidents of crop-raiding. Creating wildlife corridors to maintain the connectivity of wild ecosystems or protected areas is critical and can help decrease conflict substantially by giving wildlife access to their seasonal ranges or migration routes in ways that don’t compete directly with people. But it’s always more complicated in real life than it appears on paper!

In Tsavo, where a new high speed railway has cut through our largest national park, considerable effort went in to creating underpasses for wildlife. But to build the railway the government had to de-gazette that section of the park, so the underpasses beneath the railway suddenly became uninhabited and unprotected land. Save the Elephants has been tracking 30 elephants in the area to see how they have responded to the railway and which underpasses they use. An unforeseen outcome of the de-gazettement was that local farmers suddenly moved into the underpasses, blocking what were meant to be key wildlife corridors and forcing the elephants to climb up over the 10 metre high embankment of the railway line, breaking through the electric fences built to protect the trains, simply to avoid conflict with people. What becomes quite clear, is that any kind of development (infrastructural or otherwise) has to be carefully thought through in partnership with environmental scientists.

On the social development side, alternative livelihoods through eco-tourism, introducing people to sustainable farming practices, or regeneration of degraded landscapes, can help uplift and empower the people that live closest to wildlife, bringing benefits that they would not otherwise receive (employment, education, medical etc), all of which helps win over hearts and minds. Many eco-tourism operators offer scholarships, and secular education or training opportunities are hugely important for building local capacity and resilience. What’s important is to link everything back to the endangered/iconic species, and the role they play in maintaining ecosystem health and long term sustainability.

-

If you didn’t live and work in Kenya, where else in Africa would you live?

Many years ago, I visited the Central African Republic to film forest elephants and lowland gorillas, and fell head over heels in love with that part of the world. I was told of an area where the forest crashed into savannah, mingling species from these vastly different habitats in an intoxicating jumble, and so impenetrable that one could only travel in canoes up the rivers. Roaming militia from Sudan, Uganda and Congo would sweep through now and then wreaking havoc, but even their impact was limited thanks to the remoteness and inaccessibility of the area. It’s been top of my list ever since.

-

What do you honestly feel will happen to African elephants and their habitat in the next 50 years with the world’s current population growth. Do we need to start putting pressure on governments to encourage a slower birth rate? Controversial but surely nothing will change until the human population calms down

Until the human population levels off, and until our demands on the planet become sustainable, we’ll be fighting a rearguard action for the natural world. Each species we lose is another thread unravelling from the fabric of life, and a door in our future slamming shut. Although conservation efforts are helping slow down the rate of extinction in some areas, MUCH more needs to be done at every level, as well as a real change in how we live, breed and consume. There is still time – just – to turn things around, but we have to keep on fighting hard for nature. Human population increase is a global problem and our expanding footprint the biggest threat to the natural world. But people are also ultimately the solution, if we can harness their goodwill, intelligence, ingenuity and compassion as a force for change. The surest and kindest way to reduce birth rates is through providing education and opportunity, as well as access to good healthcare and contraceptives, but it needs to be done in a sensitive way so that both people and wildlife see the benefit. Supporting family planning initiatives is money well spent and putting pressure on governments can only help. The first steps towards real change starts in our own back yards, practicing what we preach and leading by example.

-

To what extent is the absence of tusks a genetic phenomenon? We were surprised that the three females we saw without tusks, (Cinnamon, Monarch, and one of the Rivers) were from three different families.

Some elephants are born genetically tuskless. In fact, I have the skull of one of them in camp, and you can see quite clearly the lack of “tusk-holes” where you would expect to see ivory protrude from the bone. Others lose their tusks from fighting, breakages or infection. In areas where there has been a lot of hunting for ivory, the high level of long term predation on big tuskers has resulted in a pronounced decrease in tusk size, and in some areas an increase in tusklessness. Bull elephants have much bigger and heavier ivory so tend to be targeted first by poachers, after which the large females of breeding age are targeted and onward down the scale. In the wild under natural non-poaching conditions, it is thought that only 2-4% of female African elephants never develop tusks, but a recent study of 200 known adult females in Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique, by my friend and elephant expert Joyce Poole, records tusklessness in 51% of those that survived the war (25 years or older), and 32% tusklessness in females born since the war (24 and younger).

-

Which element of running your camp do you enjoy most?

Being surrounded by so much diverse animal life is what I love best – waking to the sound of a genet cat snacking on insects in my roof or the rumble of an elephant feeding on vegetation close by my tent, lit up in the moonlight. Sometimes I see a porcupine scuffling around my veranda looking for tubers, or a wildcat scuttling past at dawn. By day the trees are full of birds and monkeys, elephants often pass right through the middle of Elephant Watch Camp, all of whom we know by name. In the evening, on my way to dinner, I’ve made a habit of searching for scorpions – we have at least nine species here – using a special ultraviolet torch that makes them fluoresce under the light, so we can watch them interacting with each other or just making their way searching for juicy caterpillars. My favourite moment ever was seeing one fat little fellow hunkered down with his tail arced over his body, using his stinger as a toothpick!

I also love working with the Samburu nomads. They are great fun, irreverent, stoic and brave, and we share a common love for this place and its wild life. They are also the best people in the world to have by your side in a crisis, and after so many years working shoulder to shoulder, we’ve been through a lot together. With our lives so intimately entwined, I’ve learnt so much from their way of life. It has been hugely educational, inspiring, and often humbling. Raising my children here, watching them absorb lessons from the wild, grow in strength and capability, and move fluently between cultures and languages, makes my heart sing.

-

What has been your most memorable observation of, or interaction with elephants?

One of the most extraordinary moments of my life was while filming desert elephants in Namibia. The crew were tucked up in their tents under some trees on the banks of a dry river, and I’d decided to drag my mattress out under the stars to sleep out on my own in the middle of the riverbed which I had been doing for the last few days. There were elephants upriver, and in my dreams I heard them shaking acacia trees to dislodge seedpods in the upper branches. So I was mentally clocking their presence but skimming in and out of sleep. Then suddenly I jolted wide awake. The moon was full and lit up the sand like a silver lake. I turned on to my stomach to look back at the camp, approximately 50m away, and saw a huge bull elephant sauntering along in the moonlight parallel to the river bank. He was oblivious to me and I thought he would pass on by, but then he stopped, and turned to look quizzically in my direction. The black rectangle of my bedroll clearly puzzled him – it was not something he had seen before. With a thumping heart I realised he was coming to investigate. I weighed up my chances, either scurrying for the scanty bushes that offered little protection or lying still and playing dead. I realised the latter was my best option. There was no way I could make it back to the crew’s camp. So I rolled onto my back so that I could keep on watching him, hearing his great feet padding towards me until his gigantic body blocked out the moon. My heart was pounding like a drum but I hardly dared to breathe. He scuffed the earth gently with a toe as big as my fist, a mere two metres from my head, then stretched out his trunk and hovered it over my chest, my face, and down my legs. Would he tusk me or crush me? My mind flipped somersaults in panic. Air whooshed up his trunk to analyse my scent in that great brain, the seconds passed, then a million heartbeats. At long last he turned, and with that slow, heavy tread, and a long whoosh of warm air as he exhaled, he carried on his way. My breath burst out ragged with adrenaline and relief, my heart flying through the tree tops, for I had been spared life by the grace of an elephant.

Catch Saba on Tour “My Life with Elephants” – See Dates and Tickets

Seen you twice before, now coming to your Cheltenham date. Looking forward to seeing you.

just sowing a seed and fantasising, and have seen your tv programme and thought that would be nice

a return to Kenya where I was born in 1953, although what memories I have were in Uganda

left in 1961

new year looking at the night sky????????

do you cater for single travellers?

seeds do grow so you never know

thanks peter

Dear Peter, Yes we cater for single travellers, your enquiry has been passed on to a sales person who will be in touch. Best Renate